In this article , we provide a practical, step-by-step guide to making software systems scalable , from a single-server setup to a fully distributed architecture.

It begins with the fundamentals of I/O performance, explaining how hardware limitations such as disk speed and network latency affect system throughput. Then it explores progressive scaling strategies, including vertical and horizontal scaling, caching, asynchronous processing, and load balancing.

Finally, it addresses the deeper challenges of distributed systems . data consistency, CAP theorem, replication, sharding, and event-driven communication .

offering clear, real-world approaches for designing resilient, high-performance application

Understanding I/O and Performance

First, you need to be familiar with the concepts related to IO . concepts like CPU cache, RAM, hard drive, and network.Network

❌❌Depending on the bandwidth of the server or the connection path, it can be very slow.

RAM

❌It’s tens to hundreds of times slower than the CPU cache — but still fast and efficient.

❌Data is stored temporarily and will be lost when the system or even the web server (IIS, Nginx, …) restarts.

✅It has a much higher capacity compared to CPU cache.

HDD/SSD

❌❌They are tens to hundreds of times slower than RAM.

✅They are the cheapest storage media with very large capacity.

✅Data is stored permanently and remains there until we delete it ourselves or the hardware gets damaged.

The slowest part of any software is the part that deals with IO, and within IO, the main problems are hard drives and network.

Since databases and files are stored on disks, every time we send a request to them, we engage the disk.

As a result, the Achilles’ heel of software is often the database and network.

This problem becomes even more serious in high-throughput systems.

That's why the CPU always goes to its cache first to get the required information and then to the RAM and then to the HDD in the next steps. Because they are slow and there is a delay between the time you request the information and when you receive it, it actually causes a delay in continuing the process.

User → CPU Cache → RAM → Disk → Network

Now let’s move to making the system scalable in practice

Imagine you have a website that works well initially when there aren’t many users.

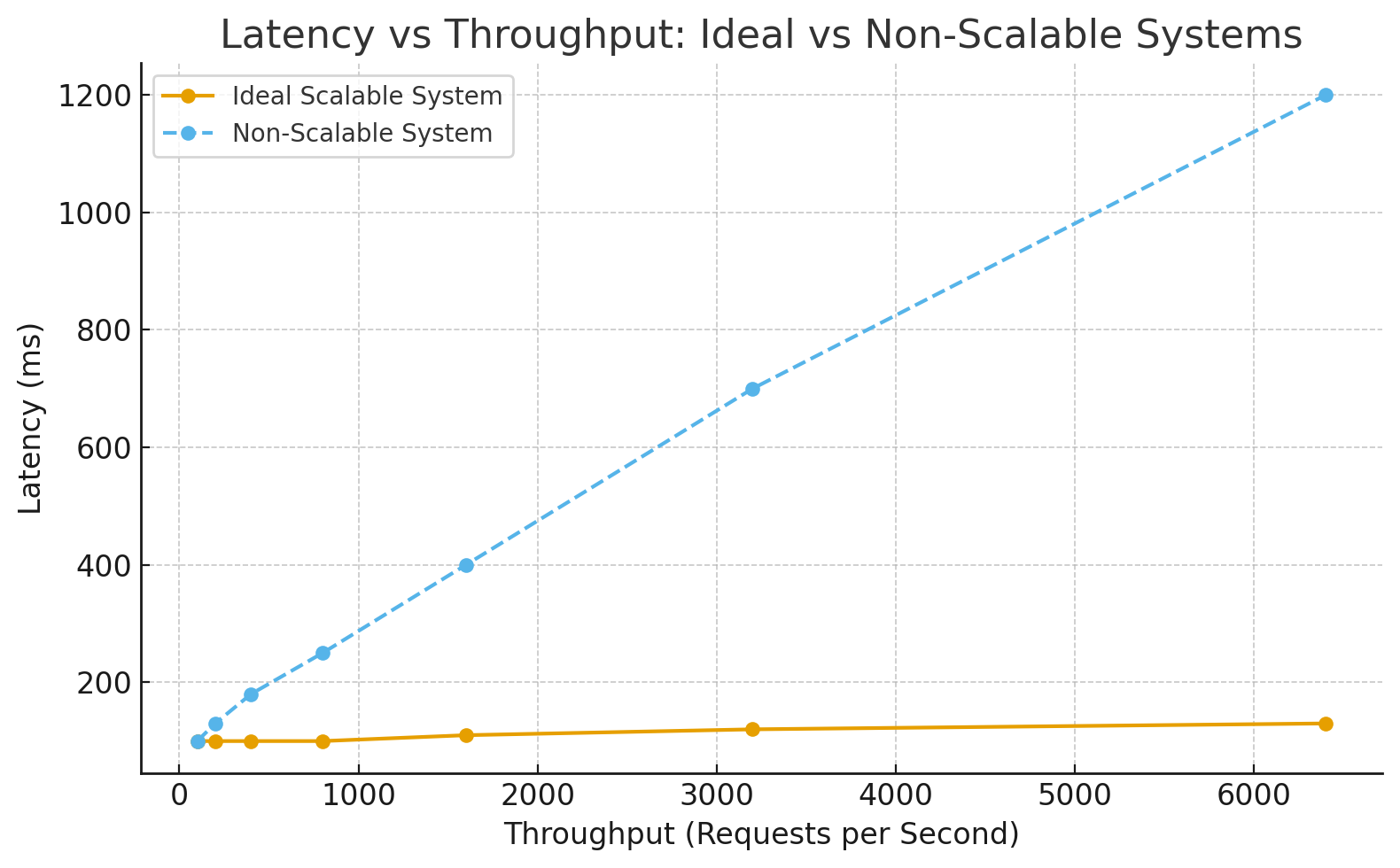

But over time, as the number of users increases, it becomes very slow , sometimes even unreachable.

That means it’s time to think about scaling.

Scaling means that as throughput increases, the response time (latency) should not increase, and the system should continue working as efficiently as before.

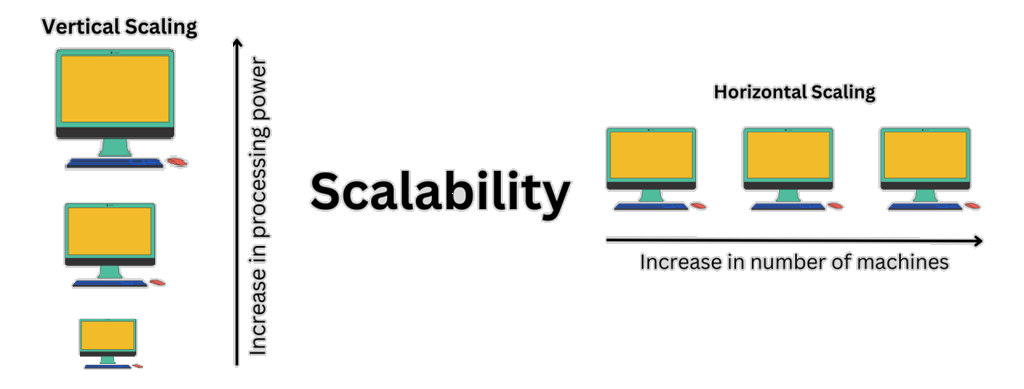

1. Vertical Scaling (Scale Up)

Upgrade the server hardware . CPU, RAM, HDD, or bandwidth of the server where the web app is deployed.

This is called vertical scaling or scaling up.

It's that simple. You see, in this method, there was no need for anything to happen from the software development team.

👉Note: When we talk about system security, we don't always mean that something has to happen from the software team. It can just include action at the hardware and network level.

Because the system is the combination of software and hardware, not just software .

2. Improve Performance with Caching

As mentioned before, IO operations (disk, database, or network) are very slow.

So we must redesign the system so that frequently used data is stored in RAM, reducing latency as much as possible.

App Server → Cache → Database3. Perform tasks asynchronously

Instead of processing all requests immediately and returning a response, defer some processing to a later time , from seconds to hours depending on the case.

For example, Microsoft Azure queues all requests, and the operation may execute 3–4 minutes later.

Client Request → Message Queue → Worker → Database4. Scale Out

Instead of upgrading the hardware of one server, deploy multiple instances of the app across several servers or nodes.

Each instance runs the same application.

Pros: Almost any kind of software with any throughput can be handled this way.

Cons: Introduces new challenges that must be carefully solved , we’ll discuss them next.

5.Distributed architectures (such as microservices)

Instead of implementing the entire software in one large application, we break it into smaller parts to make software development and resource management easier and more accurate.

In this way, each of the previous steps can be used to scale each service separately.

Scale Out Challenges and Solutions

Horizontal scaling introduces several complexities that require careful implementation

Challenge 1: Multiple instances mean multiple URLs

Clients won’t know which server to send each request to.

Solution: Use a load balancer (LB).

Clients send requests only to the LB. The LB then redirects each request to the appropriate server.

This also helps distribute network load and bandwidth across servers.

Clients → Load Balancer → Multiple App InstancesNote: Later you may see terms like reverse proxy or API gateway . for now, consider them similar since they all provide load balancing.

Challenge 2: Separate caches per instance

Each server has its own RAM, so caches are isolated.

Solution: Use a distributed cache (L2 cache).

All instances can access shared cached data regardless of which server added it.

Challenge 3: Concurrent access to shared resources (DB, cache)

Solution: Use distributed locks.

Many databases like MSSQL, MySQL, PostgreSQL, MongoDB, Redis, and Oracle support this feature.

App1 ↔

Redis Cluster

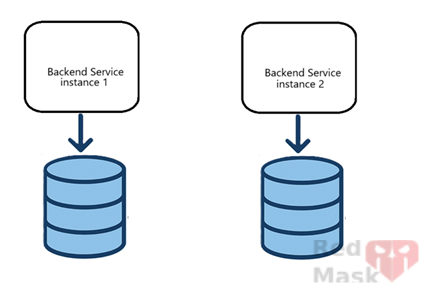

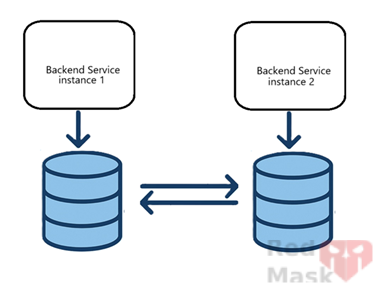

App2 ↔Challenge 4: Shared database bottleneck

Even though network IO is distributed, all instances still connect to the same database, which remains the main IO bottleneck.

Solution: Each app instance connects to its own database instance.

This distributes not only network load but also disk IO load. However, this introduces data consistency challenges such as conflicts, synchronization delay, and inconsistency across databases.

For example, data returned by server 1 should match server 2.

This is where CAP theorem and eventual consistency come into play.

Concepts we need to know include:

1.CAP Theorem

CAP stands for three properties of distributed systems:

Consistency : All nodes see the same data at the same time.

Availability : The system continues to respond to requests even if some nodes fail.

Partition tolerance : The system continues to operate even if communication between nodes fails.

CAP Rule: In a distributed system, you can only have two of the three properties at the same time.

-

CP (Consistency + Partition tolerance)

If the network breaks, availability is sacrificed to preserve data accuracy.

Example: MongoDB (majority write), HBase, Zookeeper. -

AP (Availability + Partition tolerance)

The system always responds, but data might differ temporarily between nodes.

Example: Cassandra, DynamoDB, Couchbase. - CA: impossible❌ in distributed systems

2.Eventual Consistency

In AP systems, data may temporarily differ between nodes, but eventually, if no new updates happen, all nodes become consistent.

Time →

Node A: Update → Sync → New Value

Node B: Old Value → Old Value → New ValueExample:

You have three servers, each with a copy of the users table.

When user Vahid changes his email, it might take a few seconds for all servers to update.

Some requests might still see the old value, but after a short time, all servers sync.

Used in:

-

Systems where availability matters more than instant accuracy,

e.g. social networks (posts, likes, views, etc.)

Note: Eventual consistency doesn’t mean disorder — it means delayed synchronization.

3.Strong Consistency

When data changes, all nodes immediately see the same new value.

Next readers always get the latest version.

Example:

In banking, when an account balance changes, other users must not see the old balance.

So, the system must wait for synchronization before responding — even if latency increases.

Used in:

-

Systems where data correctness is more important than speed,

e.g. banking, online payments, real-time orders.

Note: Strong consistency usually means higher latency.

Database Synchronization Methods

Methods to synchronize information between databases

1.Replication

Databases handle synchronization internally.

Two main modes:

-

Sync: Data is written to all replicas at once (slower but consistent).

-

Async: Data is written to the main database first and then replicated with delay.

You can configure:

-

Master–Slave: One DB is master (writes happen here), others replicate from it.

-

Multi-Master: All DBs act as both master and slave; whichever receives the write first propagates changes to others.

Note: While convenient, replication adds complexity and may reduce performance if misconfigured.

2.Distributed Databases

Databases that handle replication and consistency natively (e.g. CockroachDB, Yugabyte, Cassandra).

Pros: Strong distributed management and consistency mechanisms.

Cons: Complexity, cost, and operational limits.

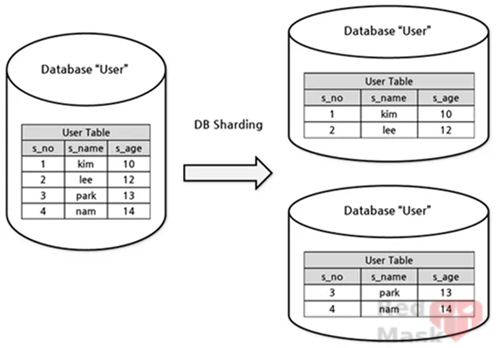

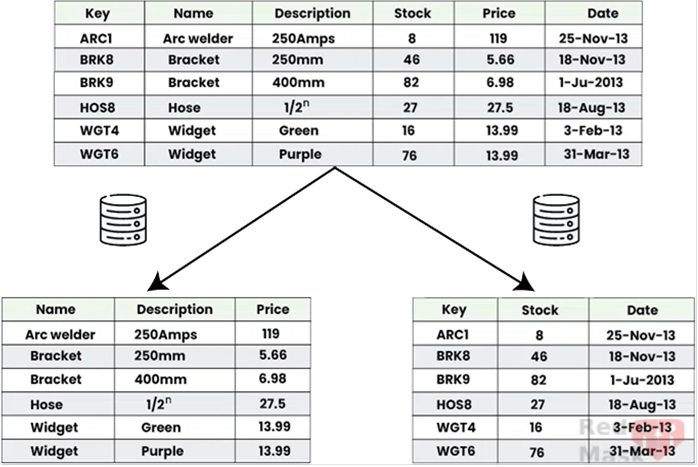

3.Sharding

Instead of keeping full copies of the same database, divide data by a key (tenant, hash, region, etc.).

Example:

Split by region — northern provinces’ data goes to DB1, southern to DB2.

Notes:

-

Each request only works with one shard (no need to query multiple DBs).

-

DB schema is identical across shards; only data differs.

-

You can periodically sync shards (e.g. during off-peak hours) if needed.

4.Partitioning

Within one service, split data between two databases:

- One stores core, frequently used data (fast access).

- The other stores less frequently used data.

So each request queries the smaller, faster DB, and only occasionally accesses the larger one.

This separation can even happen inside a single database using different tables.

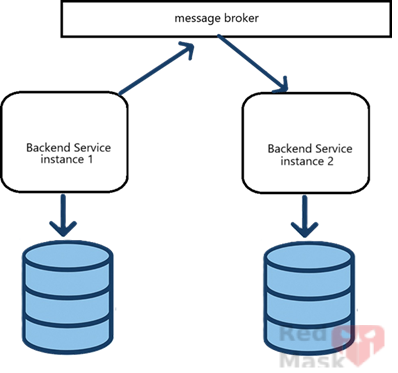

5.Events and Brokers

Whenever a request modifies data in one service’s DB, publish an event to other services.

Subscribers handle the event and update their own databases accordingly — keeping them in sync.

Drawbacks:

- Updates are not immediate (eventual consistency).

- Dependence on third-party brokers for delivery.

6.Inbox/Outbox Pattern

Instead of sending events immediately, store them in an Outbox table in the DB.

A background job later reads and sends them to the broker.

This ensures no message is lost if the broker goes offline.

On the subscriber side, use an Inbox pattern:

Received messages are stored in an Inbox table and processed later by a background job that ensures idempotency (prevents processing the same message twice).

Why? Because the broker may retry delivery, causing duplicate messages.

Summary

In short, scaling a system is like growing it step by step , from a small single-server setup into a distributed, resilient architecture. You start by fixing the obvious bottlenecks (I/O, cache, async), then scale out to multiple servers, and finally deal with the big challenges of keeping data consistent and reliable across them. The goal isn’t just to make the system bigger, but smarter. so it stays fast, reliable, and easy to grow no matter how many users come in.

A layered architecture overview showing the whole evolution:

Single Server

↓

Scale Up

↓

Scale Out + Load Balancer

↓

Distributed Cache + DB Per Instance

↓

Event-Driven + Outbox/Inbox + CAP